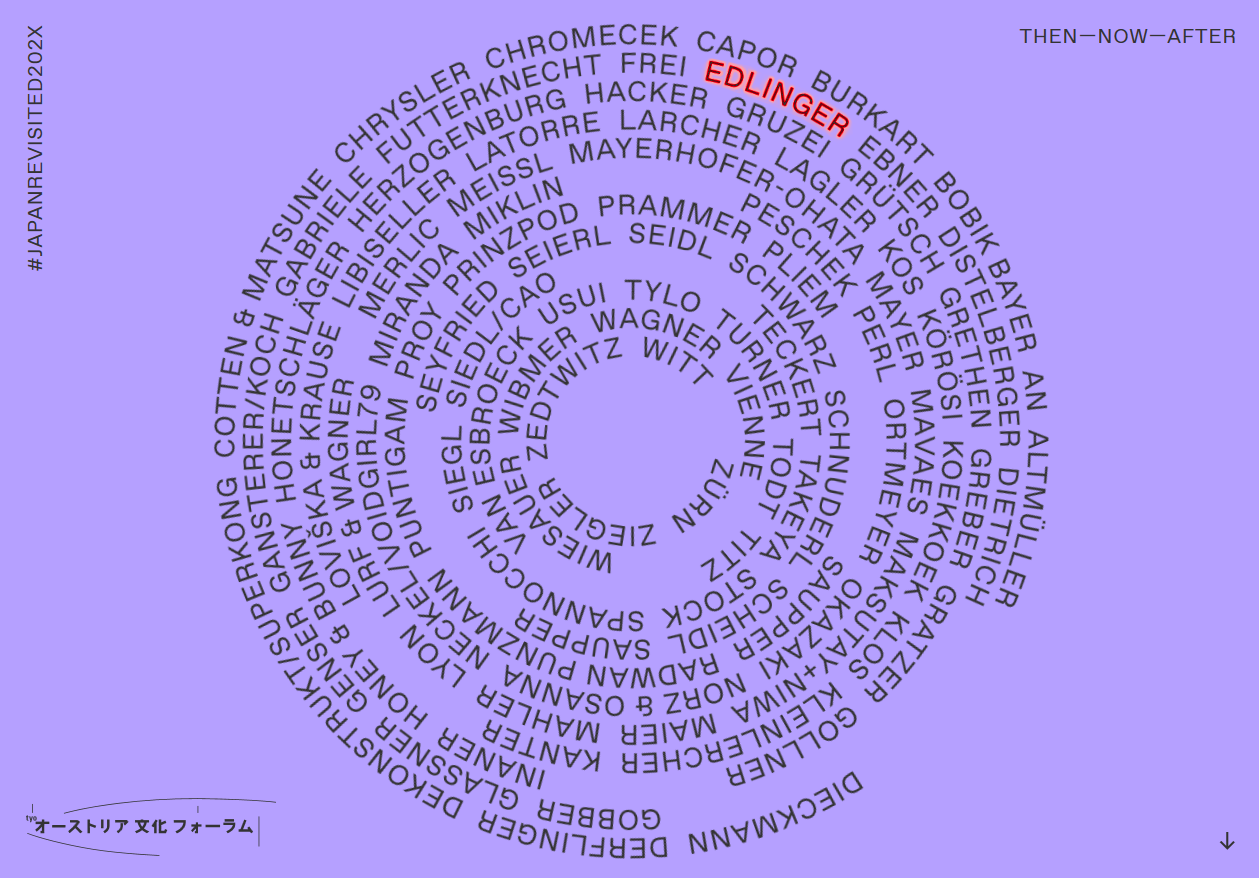

Titlepage of the online exhibition #JapanRevisited202x

On a Personal Note...

#JapanRevisited202x

Then-now-after has been conceived by the Austrian Cultural Forum Tokyo as a platform for artists from Austria to reimagine

and revisit their memories, interpretations, and dreams associated with Japan. Building on more than 150 years of cultural exchange

between Austria and Japan, the exceptional year 2020 seemed perfect for this experiment.

With works by Beni Altmüller, Yela An, Katharina Bayer, Sebastian Bobik, Hanna Burkart H.H. Capor, Julius Werner Chromecek,

Dorit Chrysler, Ann Cotten / Michikazu, Matsune Dekonstrukt/Superkong, Daniel J. Derflinger, Felix Dieckmann, Lucas Dietrich,

Akino Distelberger, Martin Ebner, Astrid Edlinger, Omani Frei, Fanni Futterknecht, Anna Gabriele, Nikolaus Gansterer / Simona Koch,

Jari Genser, Anne Glassner, David Gobber, Marlene Gollner, Anita Gratzer, Marianne Greber, Elodie Grethen, Felix Grütsch,

Katharina Gruzei, Stephie Hacker, Andreas Von Herzogenburg, Edgar Honetschläger, Honey & Bunny I Michelle Inaner, Eginhartz Kanter,

Toni Kleinlercher, Matthias Klos, Koekkoek, Viktoria Körösi, Tonia Kos, Milan Loviška / Otto Krause, Peter Lagler, Claudia Larcher,

Camilo Latorre, Julia Libiseller, Johann Lurf / Laura Wagner, Lotte Lyon, Nicolas Mahler, Marlene Maier, MaVaEs, Ralo Mayer,

Mayerhofer-Ohata, Michaela Meissl, Rebecca Merlic, Silvia Miklin, Flora Miranda, Hannah Neckel / Voidgirl79, Yelena Maksutay / Yoshinori Niwa,

Chris Norz / Philipp Osanna, Elza Okazaki, Sarah Ortmeyer, Michael Perl, Christiane Peschek, Karin Pliem, Agnes Prammer, PRINZpod,

Gabriele Proy, Werner Puntigam, Christoph Punzmann, Lucja Radwan, Judith Saupper, Chris Saupper, Roman Scheidl, Martha Schnuderl,

Iris Schwarz, Walter Seidl, Wolfgang Seierl, Günter Seyfried, Siedl/Cao, Andrea Siegl, Guido Spannocchi, Martina Stock,

Dekonstrukt/Superkong, Akemi Takeya, Christian Teckert, Lea Titz, Hannah Todt, Julian Turner, Nana Tylo, Hana Usui, Sarah Van Esbroeck,

Michael Vienne, Johann Lurf and Laura Wagner, Therese Wagner, Margret Wibmer, Rosa Wiesauer, Anna Witt, Alexandra Zedtwitz, Laurent Ziegler,

Christian Zürn.

Visit the work in the Online gallery: https://www.japanrevisited.at/

#JapanRevisited202x is a project by the Austrian Cultural Forum Tokyo.

© raumen 09/2020

Theaster Gates, Soul Manufacturing at Whitechapel Gallery 2013; photo courtesy of Dan Weill

Making Things…

…at Whitechapel Gallery, London

There is a slight irritation as I walk further into the room of Gallery 1. On a square of bare plywood shelves in waist height several wet or semi-hard clay bowls – some of them wrapped in plastic – are waiting for further handling. Inside the square, on a somewhat lowered table plane, towels, sponges, a potter‘s wheel and some other simple tools for making pottery that have escaped my memory, lie scattered. It looks like one of those join-in events for kids that are installed at summer camps or Christmas markets.

I am attracted, amazed and irritated: One of those »provincial«, artisan, participatory activities offered here in the white chapel of »high« art? And not as part of the education programme but right here, in the middle of the main exhibition space? But this is not a join-in event. Theaster Gates installs a studio for making pottery in the centre of Gallery 1 at the 2013 Whitechapel summer show »Spirit of Utopia«. The bare plywood shelves in waist height confine the work space. Inside the potter and her apprentice – when I was visiting the potter was a woman, the apprentice a young man but they told me that there are three pairs of potter/apprentice – are busy sticking handles to a cup, centring clay on the potter‘s wheel or giving explanations to passing visitors.

Outside of the shelf-square, some more plywood boards mounted to the rear wall of Gallery 1 provide additional shelf space. A round top-loader kiln placed in the opposite corner, next to the entrance, completes the studio. As it is only the fourth day of the exhibition the shelves are still mostly empty. Throughout the duration of the show all the pottery made by the three potter/apprentice couples will be dried, fired in the kiln and stored in the shelves – which should be pretty cluttered after two months of work.

Gates is thereby »investigating skill, teaching and craft« – the description in the Whitechapel summer folder sums it up neatly.

Yeah!

Finally! Finally someone is interested in craft and skill, in the way craftsmanship is acquired, in the mechanics of »making things«. Someone other than me, that is. Theaster Gates has the chutzpah to place this taboo nonchalantly in the midst of such a prominent location of contemporary art. And the curators let him do so.

What a shame I won‘t have a chance to come back and see the crockery accumulating or the apprentice gain aplomb in pulling a handle!

This said, the installation has a little drawback. The potter (at least the one who was on duty when I visited), albeit having some training as a potter, had not used those very skills and techniques she was now asked to perform and teach to her apprentice for a long time. In fact, she had practised them herself only briefly when she still was a student. This is crucial. Skill, craftsmanship, that particular ability I like to call »the knowledge of the hands«, is not something that can be acquired by reading a book or by attending a two-month crash-course or by having tried it once. It needs continuous and steady practice. Worse, it needs that which has been blemished in »Western« culture for long as the opposite of »true creativity« (and therefore opposite to the very nature of true artistic ability): boring, dull, tedious repetition.

It is precisely that kind of practice Hannah Arendt ranks lowest in her tripartite hierarchy of activities. She calls it labour. This kind of activity has been regarded so inane, so addling, so meaningless for human beings that today it has been largely automated. (Curiously it has found lofty refuge in the field of sports and fitness where the tedious repetition of one hundred push-ups is commanding our admiration rather than our pity or our disdain.) Conceded, the element of repetition still becomes perceptible in the accumulation of hundreds of similar bowls, and the slight lack of mastery in the hand of the potter will go unnoticed by the vast majority of visitors. And yet, it adds an element of hypocrisy, of »show«, that – though possibly even intended – causes this »investigation of skill and craft« to loose persuasiveness. It remains superficial in one central aspect.

This is not to argue for some kind of authenticity or truthfulness at all costs. Hypocrisy, show, display all have their righteous place and even necessity in art and in life. Playing at having a skill may well be a way of acquiring it – but playing at mastery of skill is a contradiction in itself. Imagine a footballer just pretending ball control… he vigorously mimics all the gestures – but always misses the ball…

And then – the apprentice was quick to mention it when I made a comment on the role of craft in contemporary art – what does it mean that the artist himself, despite putting craft »on stage«, does not engage in any manual labour but limits himself to organising the event and hiring the hands who will perform the task? Trying to swim without getting wet? Or just an inherent necessity that comes as a corollary of success and hence busy schedules in a demanding art world? Or a deliberate statement that, abeit picking up the ousted topic, aims at pegging its inferior position?

Or is it just to open up all these questions?

The potter/apprentice couple however was at least happy to have found a job in the arts sector that is reasonably well paid (or rather: paid at all) for a change.

© raumen 07/2013

Pedro Reyes, Sanatorium at Whitechapel Gallery 2013; photo: Astrid Edlinger

The Spirit of Utopia

Exhibition, 4 July – 5 September 2013 at Whitechapel Gallery, London

Who are we? Where are we going? What are we waiting for? – these questions from The Principle of Hope by Ernst Bloch precede the short text about the exhibiton in the Whitechapel summer folder of 2013. Big questions indeed. Yet the works shown in »The Spirit of Utopia« not only measure up to them, they reach beyond. They explore the territories of what is not yet there, not yet fully visible, still fragile. They lift the eye up to the horizons. They ask: Where do we want to go? They do not, like so many art works – contemporary and other –, beweep or critisise or analyse or reflect upon or mirror or simply show the status quo. »The crisis«. The deformations. The cruelties. The lies. With all their complex or hidden reasons. They do not put their finger into the wounds of society. They do not put on rose-coloured glasses and create lofty, aesthetic worlds of escape from harsh and ugly realities either. They do not. No. They dare to invent, to envision, to speculate. Better even, they tackle with brisk resolution that amorphous spot where worlds are in the making. They inspire enthusiasm. They are the best I‘ve seen in years in art worlds and outside of it. If you have not seen (or rather: experienced) Pedro Reyes’ Sanatorium, Theaster Gates’ studio for making pottery or Claire Pentecost’s apothecary jars full of soil examining bacterial life, (Pedro Reyes had installed his Sanatorium previously at dOCUMENTA 13), go and see it! You have time until the 5th of September 2013.

© raumen 07/2013

Gavin Turk, Chips to Go, painted bronze, 2008; photo: website Gavin Turk

Making Things I

»I just like making things« said Gavin Turk airily in the late afternoon Artist Talk on the second public day of Art Basel 2013. And indeed, despite (or rather: hence) his »reputation for challenging notions of value and the myth of artistic integrity« (Press Release, Ben Brown Fine Arts, 2013) there is a lot of »making« in his work. Particularly his painted bronze sculptures conceal a lot of skill and craft beneath their trivial and ephemeral looks.

Much of the appeal of these works, while »asking epistemological questions to trivial things« as Matthew Collings put it at the talk, is the same as the fascination of classical trompe l‘œil painting: things that pretend to be something they are not. Works that immediately – or, as in Turks case, after having read the description – prompt the observer to step closer, to look harder, to even touch and ask: How the heck was this made?

A bit later when Gavin happened to take his coffee at the same coffee bar as I did on the ample grounds of Art Basel, I asked him – with Hannah Arendt and her ranking of human activities in the back of my mind – about this love for making things, his social background and the role of skill in his work. His father, it turned out, was a jeweller. A »very traditional jeweller« as Gavin emphasised. Thus his fathers business was not going too well in the end. When I asked whether, hence, his own work could be seen as a policy to continue »making things« like his father did (in the sense of Hannah Arendts »Work« that is, as an activity that has a beginning and an end and leaves an enduring artefact) while still finding approval and financial success in today’s (art) world by putting it into a different framework, his answer was slightly evasive. »In fact, I do not need to make it all myself. I can as well commission work. But of course, I will always choose someone who has the ability and skill to realise it just the way I want. The best person for the task. And this can just as well – but need not – be me.«

Albeit evasive, the answer is still illuminating. It can be seen as part of the strategy. »Making things«, and even more »Making things skilfully« has had a bad reputation in »relevant« art for a while now. In 1913 Marcel Duchamp invented the ready-made by selecting a bicycle wheel and nominating it an object of art.

Why?

Joseph Kosuth cites Duchamp in »Editorial in 27 parts« (1991, 7-9) with the following words that can be taken as an explanation:

»In France there is an old saying, ›stupid like a painter‹. The painter was considered stupid, but the poet and writer very intelligent. I wanted to be intelligent. I had to have the idea of inventing. It is nothing to do what your father did. It is nothing to be another Cézanne. In my visual period there is a little of that stupidity of the painter. All my work in the periode before the Nude was visuell painting. Then I came to the idea. I thought the ideatic formulation a way to get away from influences.«

»Making things« means to soil one‘s hands. It means to use »the body« rather than »the mind«. The body is stupid. Manual labour makes the mind dull. It is degrading. At least this the common bias. Duchamp was strikingly aware of this. He wanted to be considered intelligent. This has not changed since. Today still, more than ever, as a contemporary artist, if you‘re able to make others make things for you, if you‘re able to successfully copy the structures of the »free market economy« that is, if you‘re able to act like an entrepreneur, it means social prestige.

So, aspiring artist, be wise! Don‘t put the emphasis on skill. Rather put it on »the idea«. Emphasise your ability to make somebody else soil his hands and do the manual work (if it is still necessary). Or even, get rid of anything in your work that requires manual skill at all. And if you should – be it by nature or nurture – enjoy »making things« and be good at it, just don‘t make a fuss about it.

© raumen 06/2013

Making Things II

»I do not like to decide …«, insisted Go Hasegawa at a talk he gave on June 5th 2013 at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. The occasion was the opening of the MAK exhibition »Eastern Promises – Contemporary Architecture and Spatial Practices in East Asia«. He accompanied these words with a shy smile and an apologetic gesture.

Whether Go Hasegawa actually continued the sentence using the exact wording, I can‘t remember. But the meaning was still the same: »I do not like to decide, I like making things«, he repeated while projecting an image showing hundreds of models for a house onto the wall of the small lecture hall. A murmur of amusement and astonishment went through the audience.

»But as an architect you have to decide in the end! How does that decision finally come about? What are your criteria for selecting one and dismissing all the other possibilities?« asked Julian Worrall, architect, writer and assistant professor at Waseda University Tokyo, in the discussion that followed. Short of a real answer to this question Go just shrugged his shoulders and replied something like: »Well, it comes just naturally at some point…« Of course some healthy scepticism is adviseable whenever »nature« and »the natural« are invoked in a discussion. Too often the invocation of the natural is a strategy to disguise mechanisms of power and to render sacrosanct situations of inequality or injustice by naturalising them.

This said, if you take a closer look at the design process decribed, »natural« here means, that decision making is delayed. It is a process much more complex and interdependant from a variety of actors and circumstances than the word decicion ordinarily implies – namely a chioce that you make after thinking carefully (Macmillan Online Dictionary). Most importantly, it does not so much involve thinking than making. It is by making that some things become decideable. Even the person who will take the responsibility for the decision in the end is not sure from the beginning. The architect here has nothing in common with the conventional and still prevailing notion of the architect as demiurg in a Platonic sense. The demiurg (in Plato and in antiquity) is a craftsman who first conceives the world (or a work) and then puts it – or often: has it put – into practice according to that preconceived plan.

The design process Go Hasegawa describes is different. It is not a cognitve process, but a process that involves the hand, trial and error, making. The making of hundreds of models in particular. It is not the mind but the hand that is always one step ahead. The mind follows.

At this point Hannah Arendt is wrong. She describes manufacturing (»Herstellen«) as a process that follows a plan – and thereby follows closely the Platonic tradition. But indeed »making something« (»Herstellen«) has to be understood much more as a dialogue between materials, techniques and the actors involved. While it is true that it can be characterised by having a beginning and an end and producing a durable artefact, it is a long standing and momentous misconception that creation (»Herstellen«) means just carrying out a pre-conceived plan or model.

In discussions with religious people – of a varietiy of different faiths and levels of education – one argument is obstinately recurring: If nature, the world, man is so manifold, so rich, so wonderfully organised as we can perceive it, there has to be a plan behind it – and a creator who made the plan. This inability to imagine creation without a plan (or a creator) is not limited to things that ultimately transcend human understanding. Even the construction of a building, a Gothic cathedral for example, cannot be pictured without a preconceived design. The transfer of Plato‘s notion of creation from craftsman, to architect and to god prohibits the notion of an emergence without a plan or a creator. It prohibits to think matter as autopoetic and the body as knowledgeable.

This prohibition has to be overcome.

© raumen 06/2013

Left: Laptop, Watch, iPhone; Photo by Brad Pouncey on Unsplash; Right: Laquer object by Heri Gahbler © Heri Gahbler

Das Verhängnis der Perfektion

Die traditionelle japanische Lack-Kunst umgibt eine Aura von Luxus, asiatischer Eleganz und handwerklicher Meisterschaft. Einerseits. Andererseits verwechseln ungeschulte westliche Touristen die teuren Lack-Gegenstände gerne mit billigem Plastik-Geschirr. Und das ist ihnen nicht einmal zu verübeln.

Die Lack-Schalen sind leicht wie Plastik, der makellose Glanz und die Glätte der Oberfläche lassen auf industrielle Fertigung schließen. Der post-industrielle Mensch verschwendet wenig Gedanken auf die Art und Weise wie die Gegenstände, mit denen er sich umgibt, hergestellt werden. Die Konsumentin nimmt es als gegeben, dass das neue iPhone makellos schwarz glänzt, dass sich die Oberflächen der Kaffeemaschinen, Laptops und LCD-Fernseher ebenmäßig und fehlerfrei präsentieren und dass es in all den elektronischen Geräten Bauteile gibt, von deren Fertigung sie sich nicht die geringste Vorstellung macht. Allein schon deswegen nicht, weil die Fertigungstechnik ob ihrer Kleinheit und Präzision die alltägliche menschliche Vorstellungskraft übersteigt. Vor diesem Hintergrund hat es die traditionelle japanische Lack-Kunst schwer. Sie entstand in einer Zeit, in der es keine industrielle Fertigungstechnik gab und in der spiegelglatte, hochglänzende Objekte so einmalig und ungewöhnlich waren, dass sie nur Bewunderung und ungläubiges Staunen hervorrufen konnten. Zusammen mit einer Ahnung wieviel Zeit und Meisterschaft wohl in diesen simplen Schalen und Boxen stecken mochte.

Wie kann jedoch heute ein solches Lack-Objekt einem naiven Betrachter vermitteln, dass hinter der glänzend perfekten Oberfläche nicht ein hochtechnischer, industrieller Fertigungsprozess steht, sondern jahre- und jahrzehntelange Erfahrung und aufwändige Handarbeit? Kenner sprechen vom »mystischem Glanz« und der »sinnlichen Tiefe« der Urushi-Oberflächen, wie sie selbst heute von keinem anderen Material erreicht werden können. Doch ich zweifle, ob diese Unterschiede für den ungeübten Betrachter augenfällig genug sind.

Wenn aber der Unterschied zwischen billigem, industriell gefertigtem Plastik und aufwändiger handwerklicher Urushi-Lackierung kaum sichtbar ist, hat die unendliche Mühe, die, unsichtbar, in den Lack-Objekten steckt, dann noch irgendeinen Sinn? Anders gefragt, wohnt die Art der Herstellung dem fertigen Objekt in irgendeiner Form noch inne? Oder, falls diese Frage mit »Nein« beantwortet werden muss, ist die Frage nach den Bedingungen der Herstellung ungeachtet der Eigenschaften des fertigen Objektes von Bedeutung?

© edlinger 02/2013

Urushi-Objekt, Detail; Foto: Astrid Edlinger

Urushi

Urushi-Lack und Design. East meets West. Eine kleine Ausstellung in der Pinakothek der Moderne/ München von 12. Dezember 2012 bis 24. Februar 2013.

Empfehlenswert nur für Urushi-Aficionados, die über postmodern unerträgliche Formen großzügig hinwegblicken können. Man muss sie suchen in den weitläufigen Räumlichkeiten der Pinakothek der Moderne, die kleine Ausstellung von Urushi-Objekten. Erst ganz im letzten Winkel des Untergeschoßes, nachdem man sich einen Weg durch die halbe Designgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts gebahnt hat, wird man fündig. Und trotzdem enttäuscht. In etwa einem dutzend Glasvitrinen stehen unscheinbare schwarze Objekte. Auf einem kleinen Podest vier etwas größere Objekte ohne Vitrine. Und das war’s dann auch schon. Die Formgebung der Objekte stammt vom 2007 verstorbenen österreichisch-italienischen Designer und Architekten Ettore Sottsass, ist unerträglich postmodern und keiner weiteren Rede wert. Die meisten Besucher – zur Zeit meines Besuches vorwiegend Schulklassen – laufen folglich an der Ausstellung vorbei, ohne weiter Notiz davon zu nehmen. Dennoch hat sich der Aufwand einer Eintages-Reise nach München für mich gelohnt. Meine Erkenntnis: Es ist tatsächlich möglich, große, ebene Urushi-Oberflächen perfekt und völlig einheitlich spiegelblank zu polieren. Ohne die Schlieren, Streifen, Kratzer und »tauben« Stellen, die meine Objekte aufweisen. Der Katalog zur Ausstellung erläutert wie: Die Arbeitsschritte MIGAKI (Polieren) und FUKI-URUSHI (Auftragen von hochqualitativem, rohem Urushi-Lack in hauchdünner Schicht mit Tampontechnik) nach dem ROIRO-NURI (Schwarz-Lackieren) müssen nicht nur einmal (wie in meiner japanischen »Urushi-Bibel« beschrieben), sondern, je nach Bedarf, bis zu zehn mal oder öfter ausgeführt werden. Aha! Neben dieser praktischen Erkenntnis stellte sich nach und nach noch eine andere, grundlegendere, ein, die ich in einem anderen Beitrag näher ausführen möchte.

© edlinger 12/2012